Shock absorption: 3 signs the economy is picking up from here

The Federal Reserve (Fed) cut interest rates for the third meeting in a row this week. In their commentary, the committee members suggested that they don’t see room for many more cuts in the near future and that the economy will likely hold up in 2026. We agree.

Here’s how shock absorbers have helped keep the economy on track and why we see the potential for growth to be firmer in 2026 than it was this year.

The labor market bent but didn’t break

Coming from a place of strength at the beginning of 2025, the labor market has absorbed the tariff shock. The unemployment rate currently stands at 4.4%, higher than the 3.5% rate in January but close to what we think is the peak.

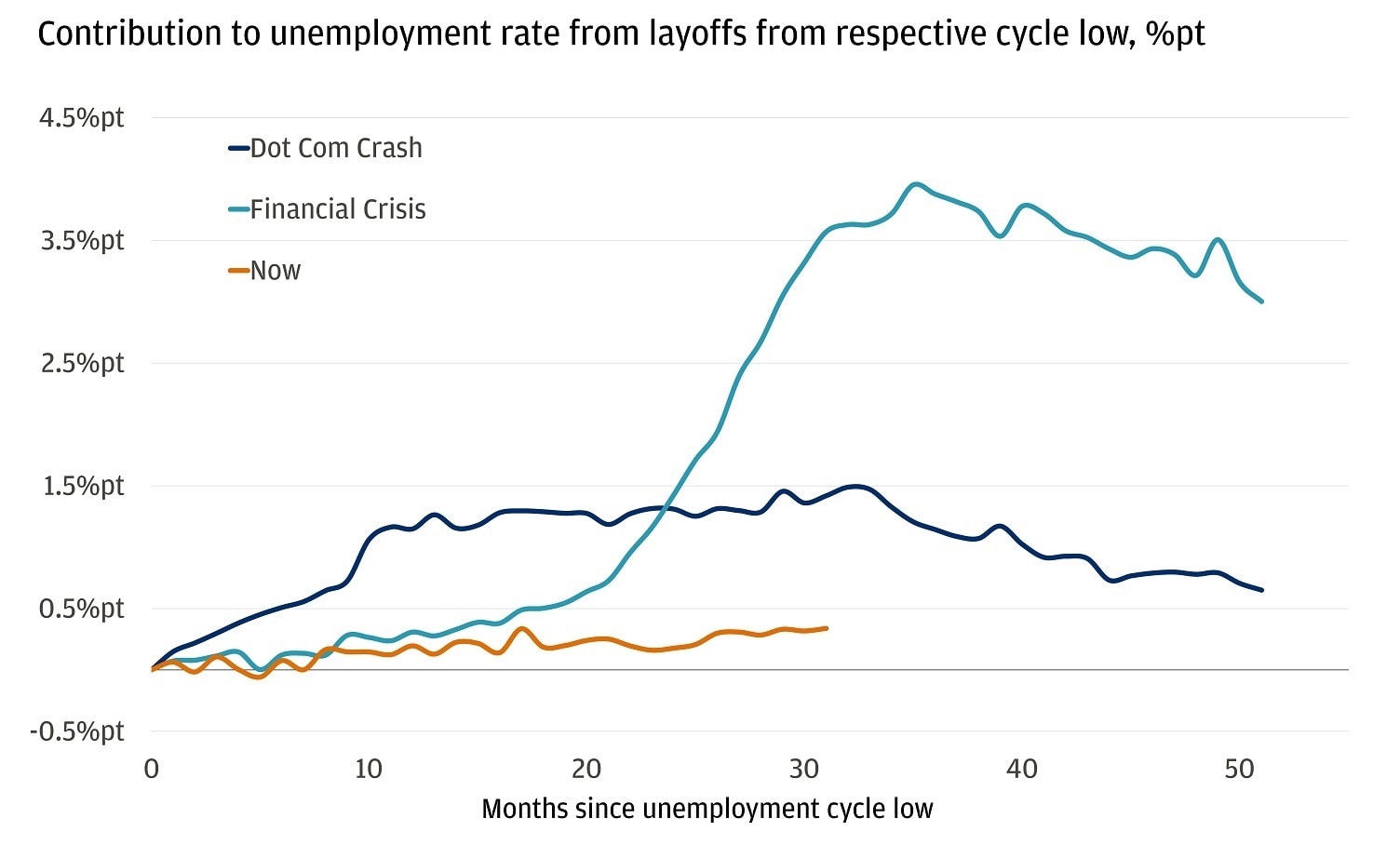

Most of the increase is from more people coming into the labor force or finishing temporary jobs, not companies slashing headcount. That’s a key difference versus a classic recession, where layoffs usually explain most of the jump in unemployment. This time, layoffs have only added a sliver to the rate so far, much less than at a similar point around the dot-com bust or the Great Financial Crisis.

Current rise in unemployment driven much less by layoffs

With the power that it has, the Fed is trying to engineer a looser, more two-sided labor market that takes pressure off wages and inflation, not a collapse in jobs. And some of the latest job-openings and hiring-plans data suggest that this softening may already be starting to level off rather than accelerate.

On top of that, incomes are still moving in the right direction. Paychecks are still growing roughly one percentage point faster than prices, so the average worker’s purchasing power is holding steady. Household cash flow isn’t booming as it was right after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it looks solid enough to keep spending growing.

What it means: The labor market has bent, not broken. As long as most people keep their jobs and real incomes stay slightly positive, the consumer can hold up – and so can the expansion.

Ready to take the next step in investing?

We offer $0 commission online trades, intuitive investing tools and a range of advisor services, so you can take control of your financial future.

Policy is shifting from headwind to neutral

The policy mix isn’t fighting the economy the way it was a year ago. Instead of asking how much tighter things can get, we’re now debating how gently policy can ease from here. That matters because the big adjustment to higher mortgage rates, a stronger dollar and tighter credit has largely already happened – the incremental hit is fading rather than building.

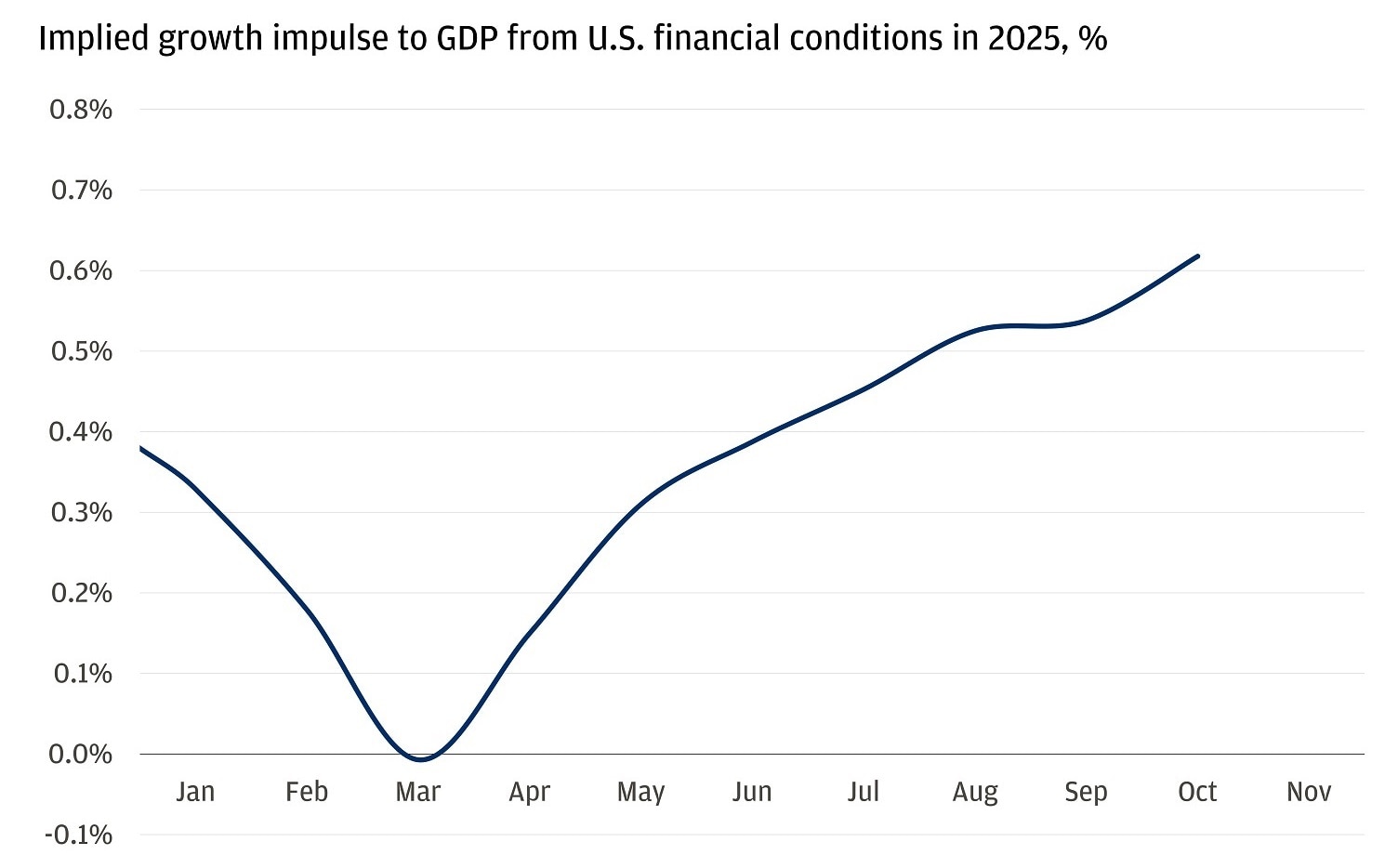

The effects of lower interest rates and easier policy are starting to work through the economy, which should help support growth. Easier financial conditions – seen in higher equity prices, tighter credit spreads and a weaker dollar – should provide an additional boost. Economists track these factors with “financial conditions indices,” which now look mildly supportive rather than restrictive. The Chicago Fed’s index, for example, implies about a 60-basis-point lift to gross domestic product (GDP) growth over the next year. In other words, financial conditions are no longer a drag; they’re starting to lean the other way.

Financial conditions are becoming more supportive

There’s also a shift on the fiscal side. This year was largely about fiscal tightening due to tariffs, but looking ahead, several tailwinds are emerging. Betting markets now assign a high probability to a court ruling against the current tariff structure and a lower probability that the Trump administration will be forced to pay out large refunds. That combination would help limit fiscal disruption and ease some of the growth drag from tariffs. In our view, this would be broadly supportive for U.S. capital over time – another sign that some of the policy headwinds are at least starting to slow.

On top of that, personal tax refunds linked to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act should begin to show up more meaningfully in household bank accounts. This effectively acts as a targeted transfer: It lifts disposable incomes at the margin, and a good chunk of that money is likely to be spent rather than saved, especially for middle- and lower-income households. It’s not a stimulus boom, but it’s one more buffer that could help keep consumer demand from rolling over.

What it means: Taken together, policy is moving from a clear headwind toward neutral, with some elements even providing a mild tailwind now. We believe this will help drive growth and give the expansion a firmer footing.

The investment cycle is still doing a lot of the heavy lifting

The U.S. is still a consumer-driven economy – household spending is roughly two-thirds of GDP, and that hasn’t changed. What has changed is where a lot of the growth is coming from at the margin. In this phase of the cycle, the investment side of the economy is doing an unusually large share of the work.

In GDP terms, this shows up as nonresidential fixed investment – basically, the money businesses spend on long-lived stuff: buildings and factories, data centers and warehouses, machines and equipment, and the software and intellectual property that sit on top. It’s a relatively small slice of the pie, but lately it’s been punching well above its weight in driving growth.

Over the last few quarters, nonresidential fixed investment has at times contributed up to a quarter of real GDP growth. That’s a stark shift when you remember that, over time, it usually accounts for closer to around 15% of growth. In other words, something that’s normally a supporting actor has briefly become one of the main characters.

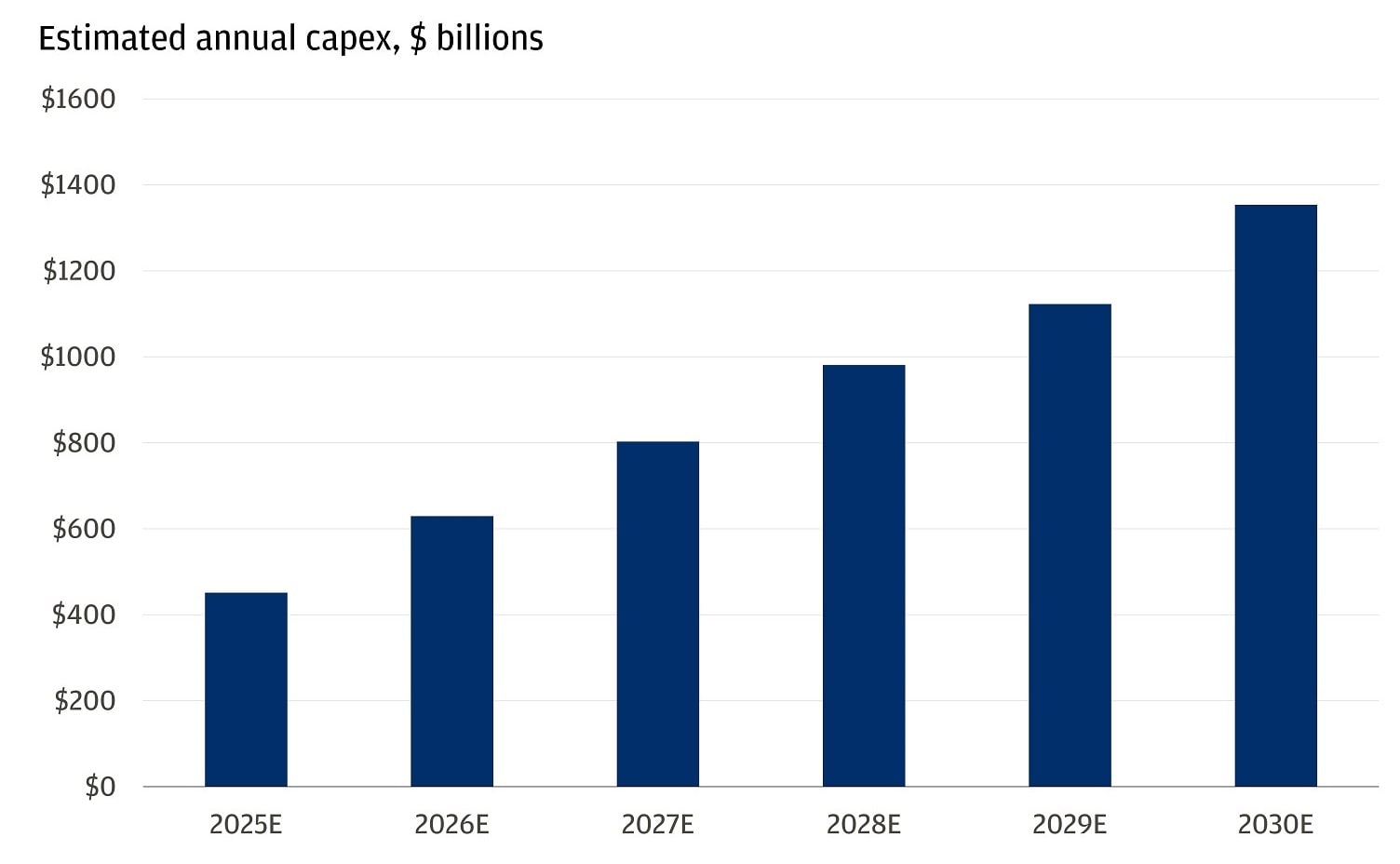

We believe this surge in nonresidential investment marks the beginning of another major capital expenditure (capex) wave. Our investment bank estimates that capex related to artificial intelligence (AI) will total around $500 billion this year and rise to roughly $700 billion next year, as firms keep building out data centers, chip capacity, power infrastructure and networks. Looking further out, we estimate funding needs in 2030 will be in excess of $1.4 trillion a year. These are multiyear commitments, not marketing experiments – once you start a data-center campus, a chip factory or a grid upgrade, you generally finish it.

Hyperscaler spending is expected to keep surging

All of this also comes with a potential productivity kicker. As companies invest in automation, software and AI tools, even modest efficiency gains would make it easier for the economy to grow a bit faster without reigniting inflation—exactly the backdrop the Fed is trying to nurture.

What it means: The U.S. hasn’t stopped being a consumer-led economy, but capex is now stepping up as a genuine second engine. With investment set to accelerate next year, we’re optimistic that capex will help keep growth on track, even if the consumer slows.

The bottom line

Putting it all together, we expect U.S. economic growth to be stronger next year than it was this year. The labor market remains resilient, policy is shifting from headwind to neutral, and a powerful capex wave around AI and infrastructure is providing a second engine for expansion. In fact, reflecting our confidence in the strength of the economy, we’re only expecting one more rate cut next year – while investors are pricing in more than two. Given this backdrop, we prefer risk assets like stocks to bonds and believe investors should consider real assets like infrastructure to help mitigate the impact of inflation.

All market and economic data as of 12/12/25 are sourced from Bloomberg Finance L.P. and FactSet unless otherwise stated.

For important disclosures, please refer to the disclosures section for detailed information.

You're invited to subscribe to our newsletters

We'll send you the latest market news, investing insights and more when you subscribe to our newsletters.