How AI can boost productivity and jump start growth

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a revolution, the optimists say. AI is a bubble, the skeptics reply. We think AI’s impact could be truly transformative, as we discuss in our 2024 Mid-Year Outlook. The path ahead is uncertain. But powerful forces could drive AI forward.

In this article, we apply an economist’s perspective to an issue at the heart of the optimist-skeptic debate: How might AI impact the overall economy? Among the questions we tackle:

- How much of a productivity boost could AI deliver? And how quickly might it arrive?

- What jobs might be displaced, and how might policymakers respond?

- Will AI be inflationary or disinflationary?

- What will be the pace of corporate adoption?

Along with a macro outlook on the potential for AI, and particularly for generative AI, we also consider the prospects for investing in this powerful trend. Although valuations on AI stocks have had quite a run, we don’t see signs of a bubble. And while AI-related companies now account for a relatively high share of the overall U.S. market, we don’t think market concentration is necessarily a cause for concern. In short, you may find a wide range of AI-related investing opportunities to consider now and in the years ahead.

Interested in working with an advisor?

Work 1:1 with our advisors to help build a personalized financial strategy that’s built around you.

Productivity and growth: How soon, how fast?

In assessing AI’s economic prospects, productivity is a key metric. Faster productivity growth allows the economy to grow more rapidly, and living standards to rise more rapidly, without generating excess inflationary pressures.

The U.S. economy hasn’t experienced sustained productivity gains since the 1990s. A reprise of 1990s-style productivity gains could usher in a new era of economic growth.

To understand how AI might (or might not) transform the economy, we consider historical precedents.

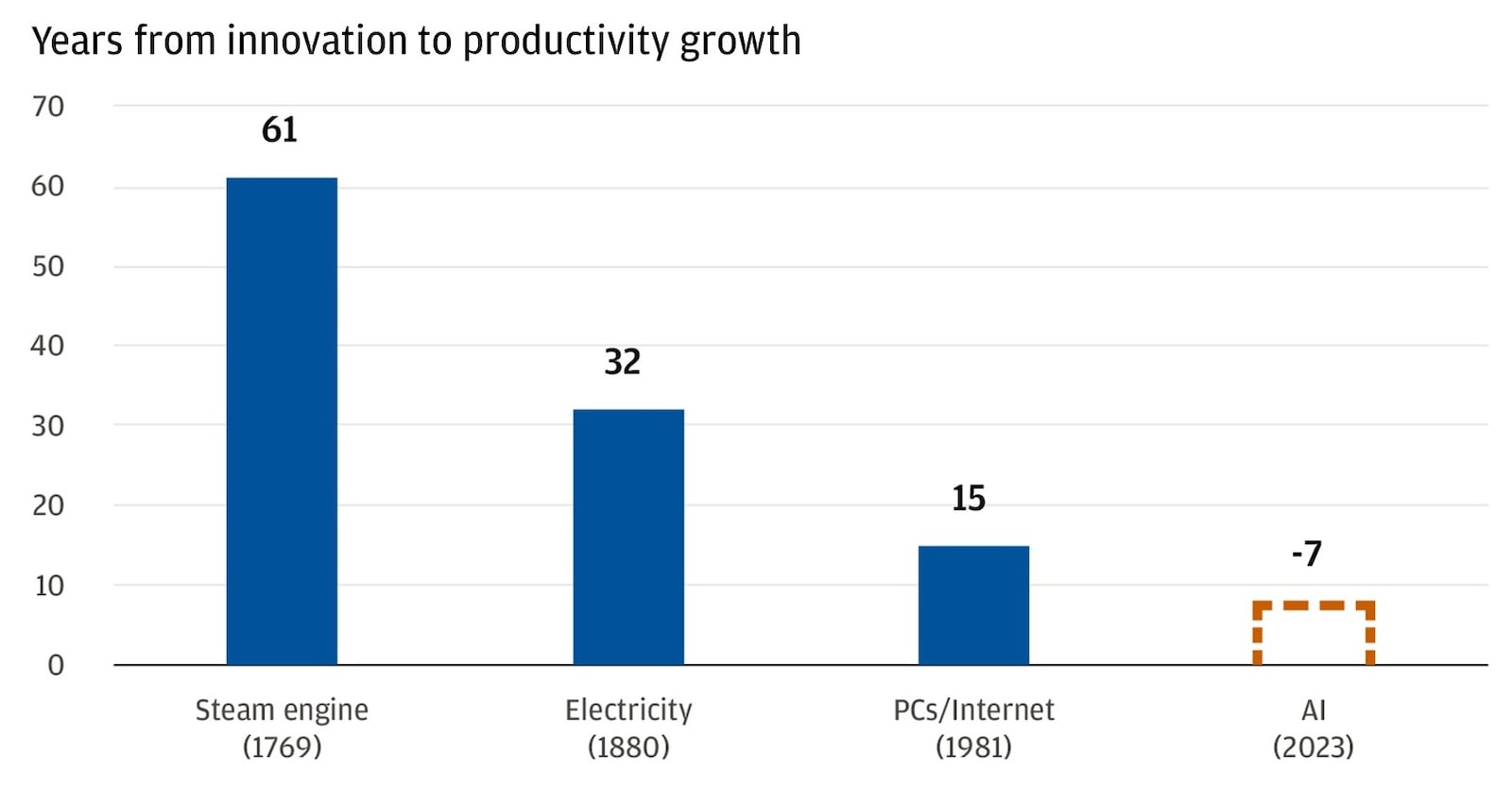

In his 2024 shareholder letter, our Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon likened AI to the steam engine, electricity and the personal computer. Looking at those episodes of technological innovation, we see that productivity benefits don’t appear overnight.

It took more than 60 years for the steam engine to deliver any observable economy-wide productivity benefit. With each subsequent technological innovation, productivity gains came more quickly.

If the trend holds, and we think it will, by the end of the 2020s, evidence of AI’s productivity boost could show up in U.S. economic data. Think of it this way: It took 15 years for the personal computer to increase the economy’s productivity. AI could do it in seven.

The timeline from innovation to productivity growth has been shrinking

Is AI the 21st century equivalent of the steam engine or electricity, each of which radically changed the economy? Probably not. But we do think AI has the potential to be as transformative as the web and personal computer, delivering even more economic value over the next 20 years.

The internet delivered a powerful productivity boost, but AI will likely surpass it

Quantifying job displacement

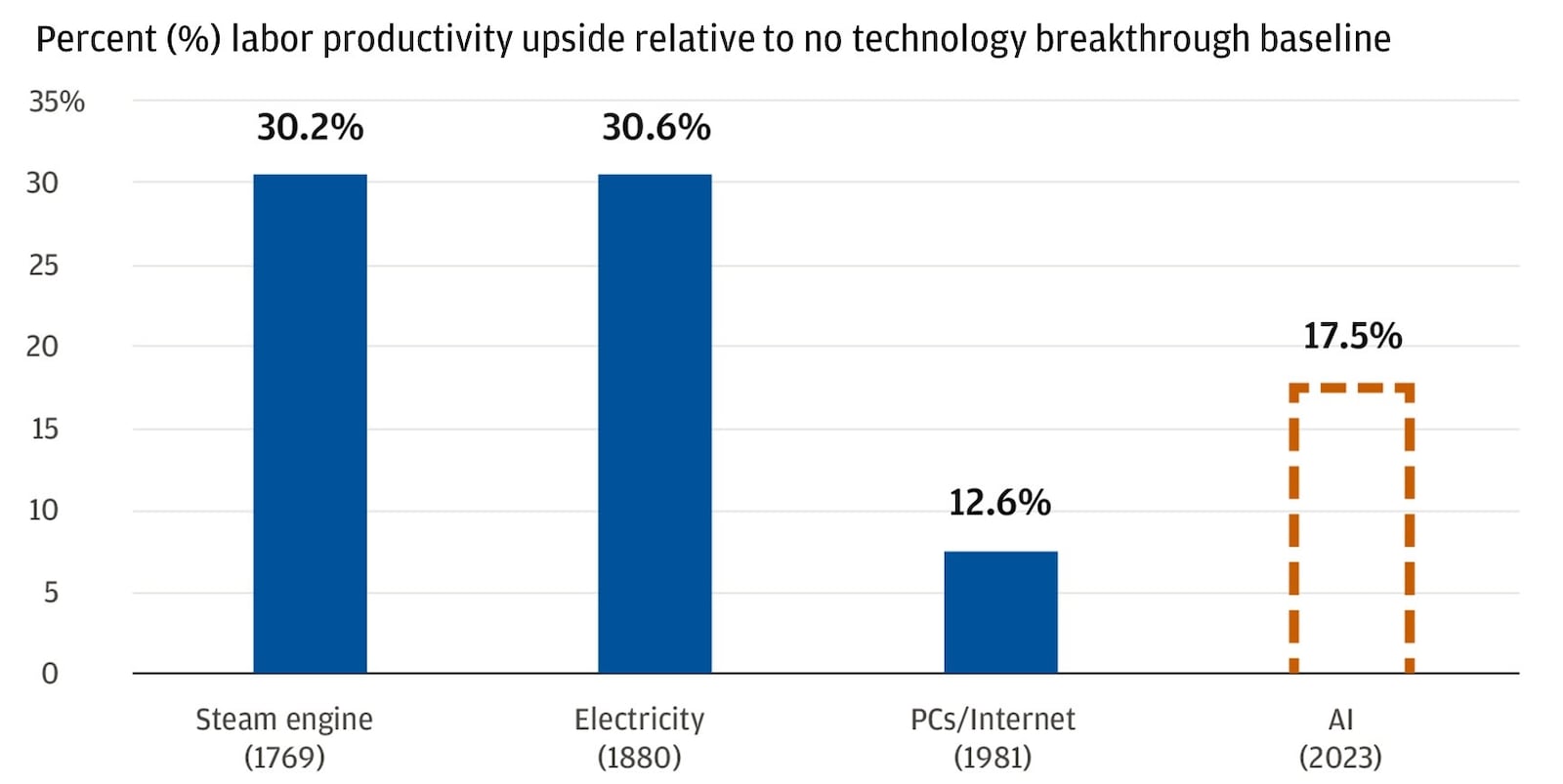

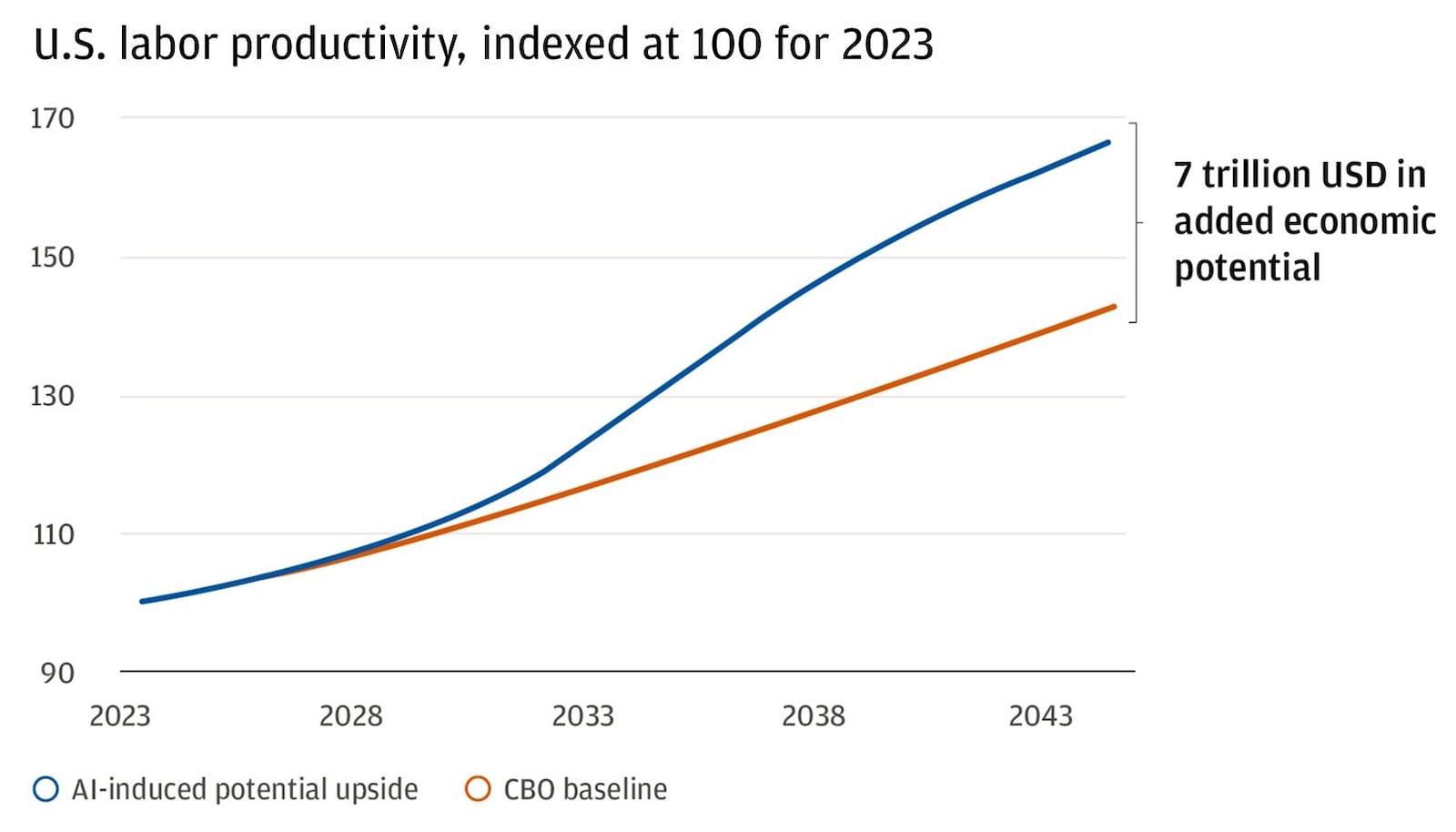

To quantify the potential impact of AI, we modify an International Monetary Fund (IMF) framework. We conclude that AI’s impact could be much greater than the productivity assumptions baked into projections by government agencies such as the Congressional Budget Office.

The IMF identifies which jobs could potentially be displaced by AI. We assume that half of the vulnerable jobs in the United States will be automated away over the next 20 years. The cumulative productivity gain would be about 17.5% or $7 trillion beyond the current Congressional Budget Office projection for gross domestic product (GDP).

What happens if half of vulnerable jobs in the United States are automated away over 20 years?

It's important to remember that technological innovation tends to boost overall economic productivity only when it changes the amount of labor and capital needed to create a given service or product in the economy. So, for example, Uber did not change the labor-capital inputs (still one driver, one car). But driverless cars, if they eventually appear on our roads, could.

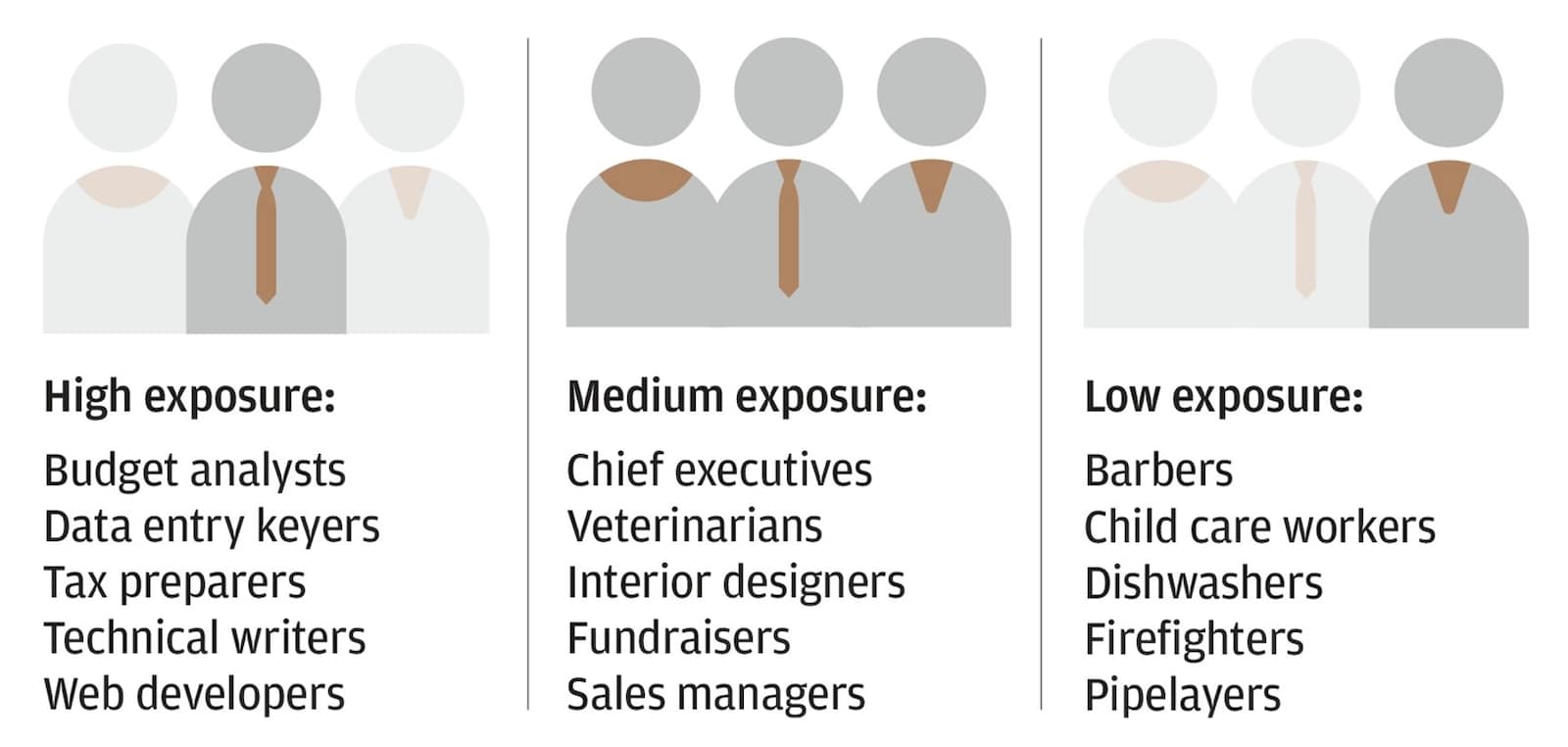

What jobs could be most at risk of AI displacement? Not surprisingly, white-collar professional service jobs such as budget analysis and technical writing look more vulnerable than child care work or pipelaying.

We also expect to see an educational divide. A Pew Research Center study concludes that workers with bachelor’s degrees or higher are more than twice as likely to be in jobs exposed to AI than those with only high school diplomas. The chart below is illustrative:

Jobs in United States that are likely to have high, medium or low exposure to AI

Across the global economy, AI will likely impact some economies more than others. The IMF has found that workers in advanced economies are more vulnerable to AI displacement than those in emerging market economies. For example, the IMF estimates that 30% of U.S. jobs could be displaced by AI versus less than 13% for India.

All estimates and projections, including our own, should be taken with a grain of salt. No one can precisely predict AI’s economic trajectory, and estimates of AI’s economic impact vary widely. A specific uncertainty relates to the cost of implementing AI technologies in the workplace. Already we are seeing infrastructure costs related to the buildout of AI computer platforms spiral higher. Just because a particular job can be automated using AI technologies doesn’t mean it will be if it’s not cost-effective.

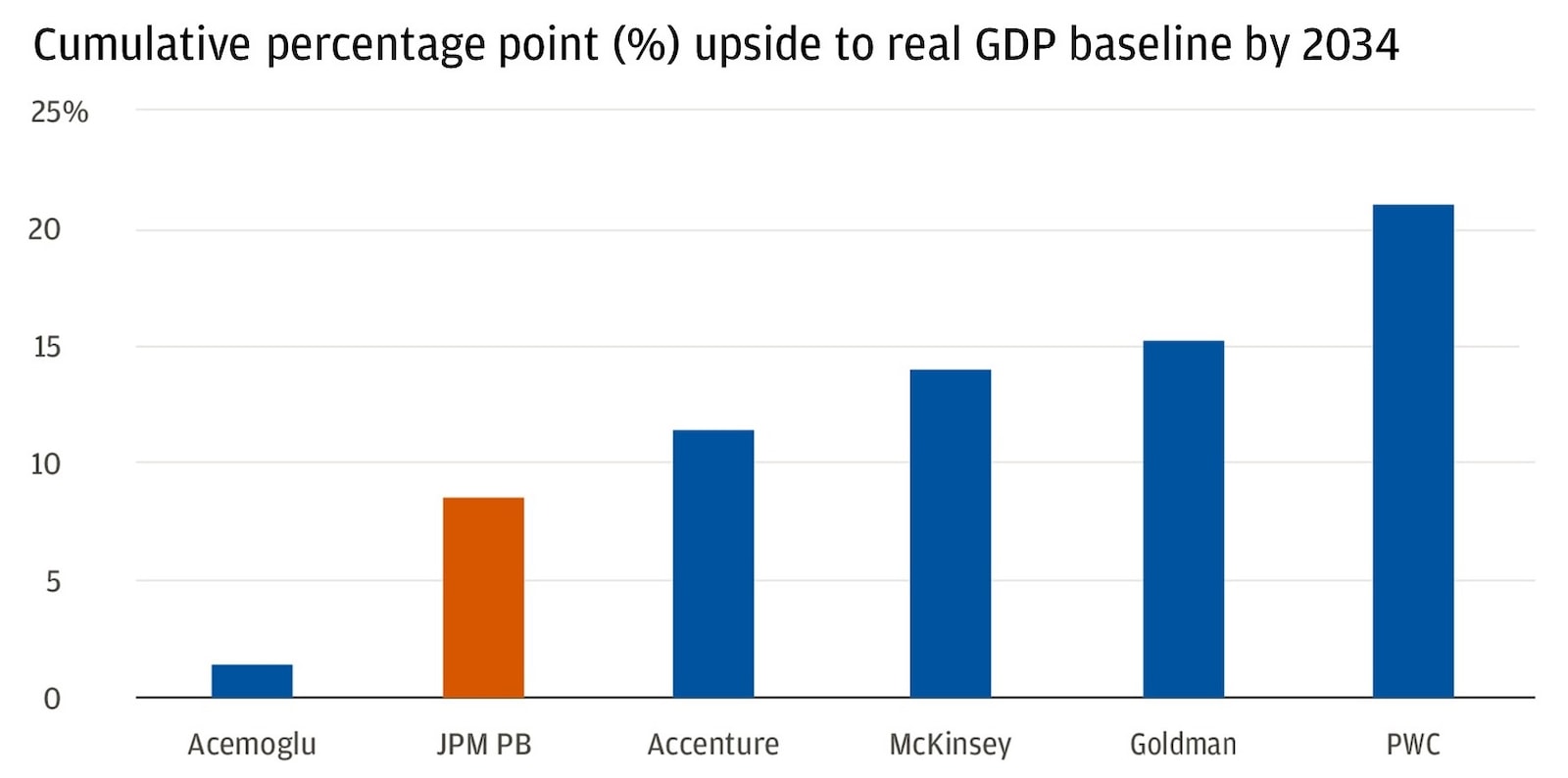

Among the optimistic prognosticators, Goldman Sachs projects a 15% boost in GDP from AI over the next 10 years. Our estimates are a little more tempered; we see an 8% to 9% increase to GDP over the next decade. MIT economics professor Daron Acemoğlu takes a much more circumspect view of AI’s potential macro impact, projecting only a 1%-1.5% boost to GDP over the same time span.

Economists make varied estimates of how AI will impact growth over the next decade

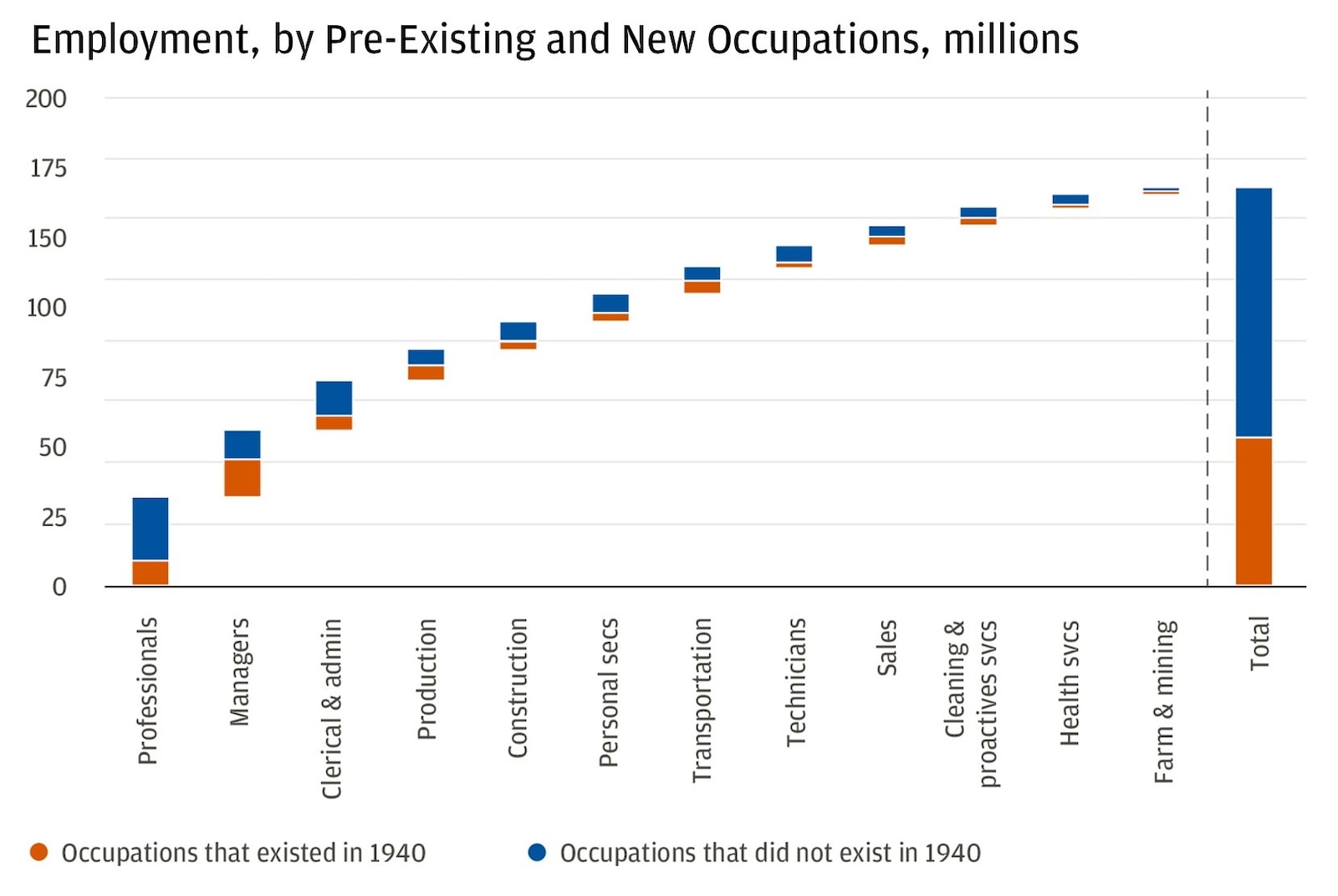

We should also remember that economies evolve in ways that may be best understood in hindsight. According to a study by economists at MIT, more than 60% of today’s U.S. job occupations didn’t even exist in 1940.

New technologies explain much of that change. Through each successive technology transition, aggregate demand increased and the economy created jobs that didn’t previously exist. The chart below shows the pattern of that change:

History tells us that technology continuously creates new jobs as old ones disappear

Policymakers will need to respond to the societal challenges AI poses. Public policy focused on job training and transitioning vulnerable workers will likely be needed to minimize the upheaval from a greater pace of job displacement.

Challenges to corporate adoption

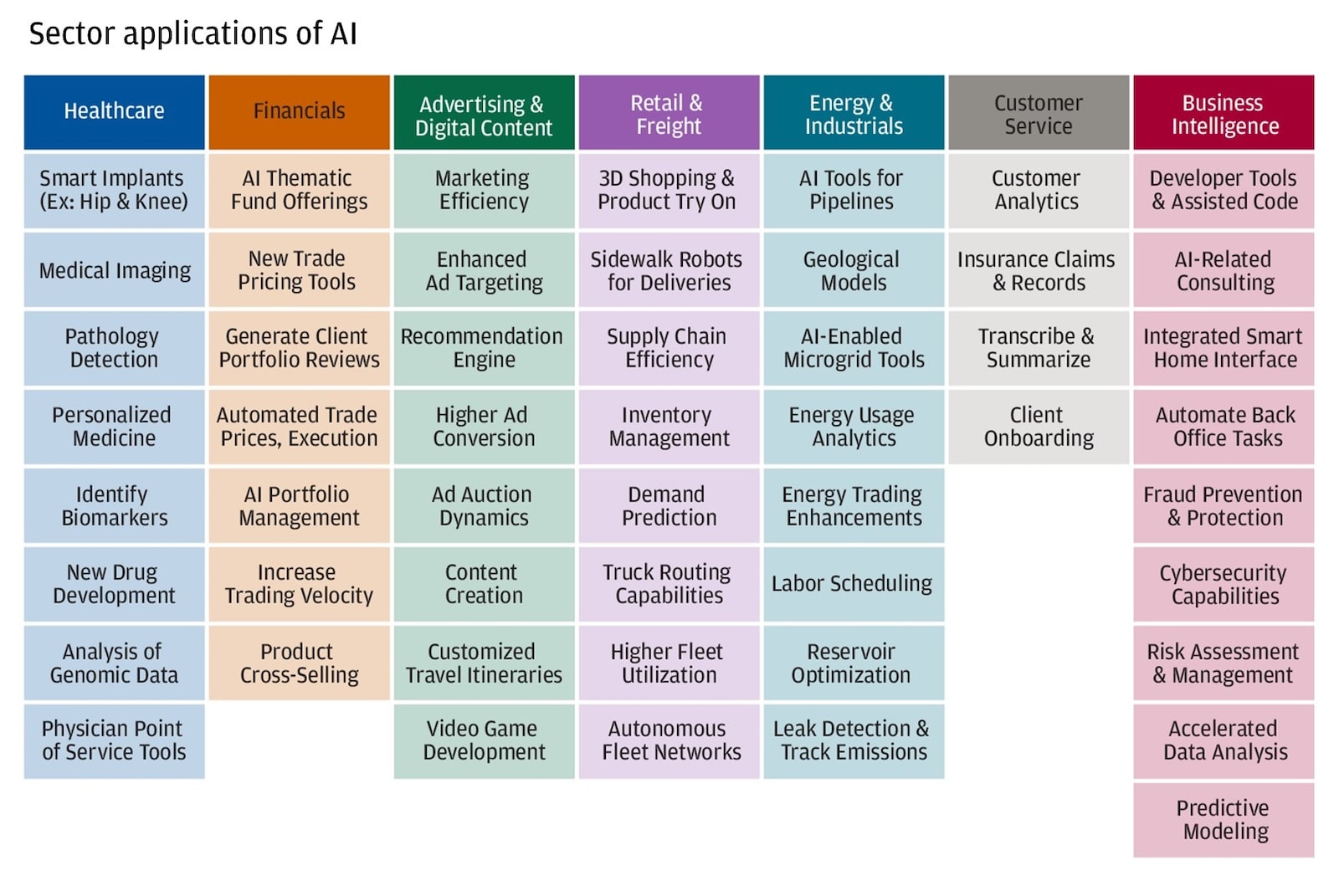

Next, we shift our perspective from the broader economy to sectors and companies. AI’s economic impact will depend on whether (and how) CEOs and management teams make AI a critical part of their business strategies and operations. Right now, it’s early days.

While most U.S. companies are considering how they could use AI, so far only about 4% of companies have actually adopted the new technology. We think adoption rates need to rise to 50% or higher before AI-driven productivity will start to impact the overall economy.

Adoption faces many headwinds. These include: concerns around the supply of advanced semiconductors, legal and regulatory issues, potentially limited power and energy resources for data centers, and firms’ ability to optimize potential use cases.

Still, the technology makes possible a wide array of potential use cases across various industry sectors. That’s what gives AI the potential to have broad macro implications for the U.S. economy.

The table below highlights the potential use cases:

AI is likely to increase revenue sources, reduce time to market and lower costs

Investing in the infrastructure buildout

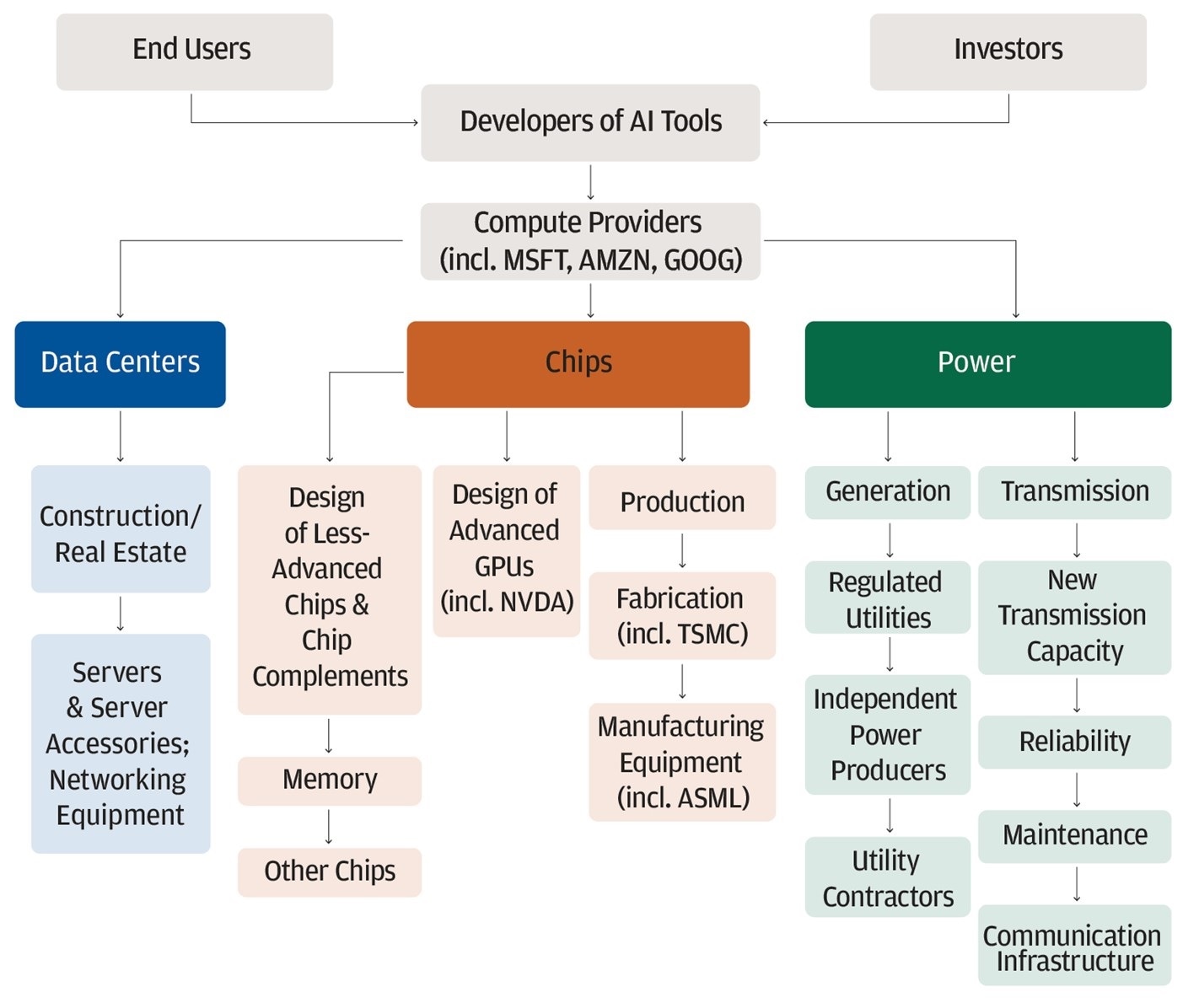

Many of these use cases will develop over time. But an immediate need is already evident: AI-related activities require extensive new infrastructure. That infrastructure falls into three categories: semiconductors, data centers and electricity power generation. (In an oft-cited example of AI’s thirst for power, a query on OpenAI’s ChatGPT LLM requires 6–10 times more electrical power than a Google search.)

The AI infrastructure buildout mapped out

While most investors focus largely on the need for more semiconductors, demand is likely to increase for other parts of the AI infrastructure supply chain as well. These include: data center real estate, engineering and construction firms, copper wire to transmit electrical signals, nuclear and renewable power to support energy requirements, cooling technologies to offset heat produced by the servers and the electrical components used to connect it all.

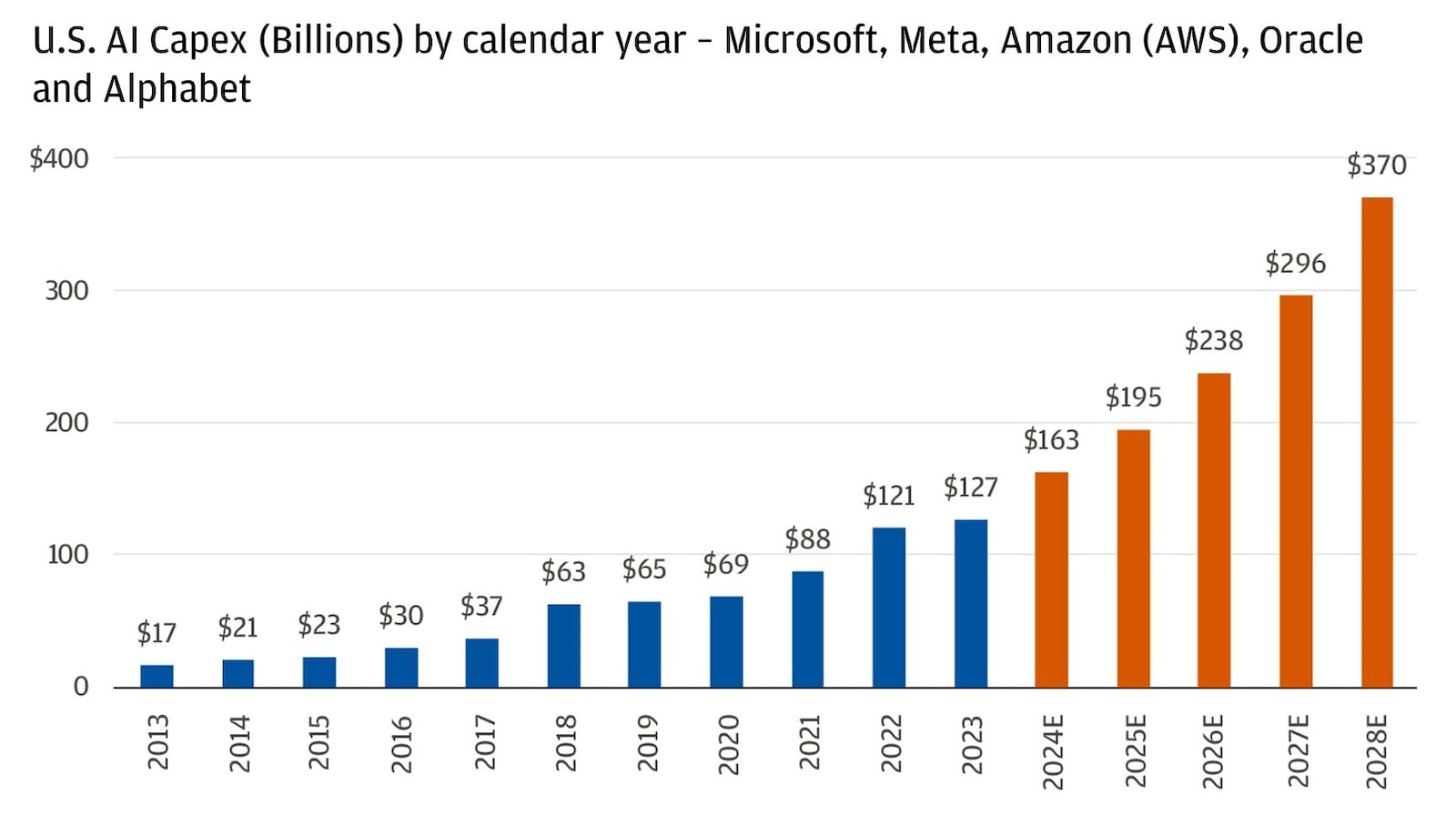

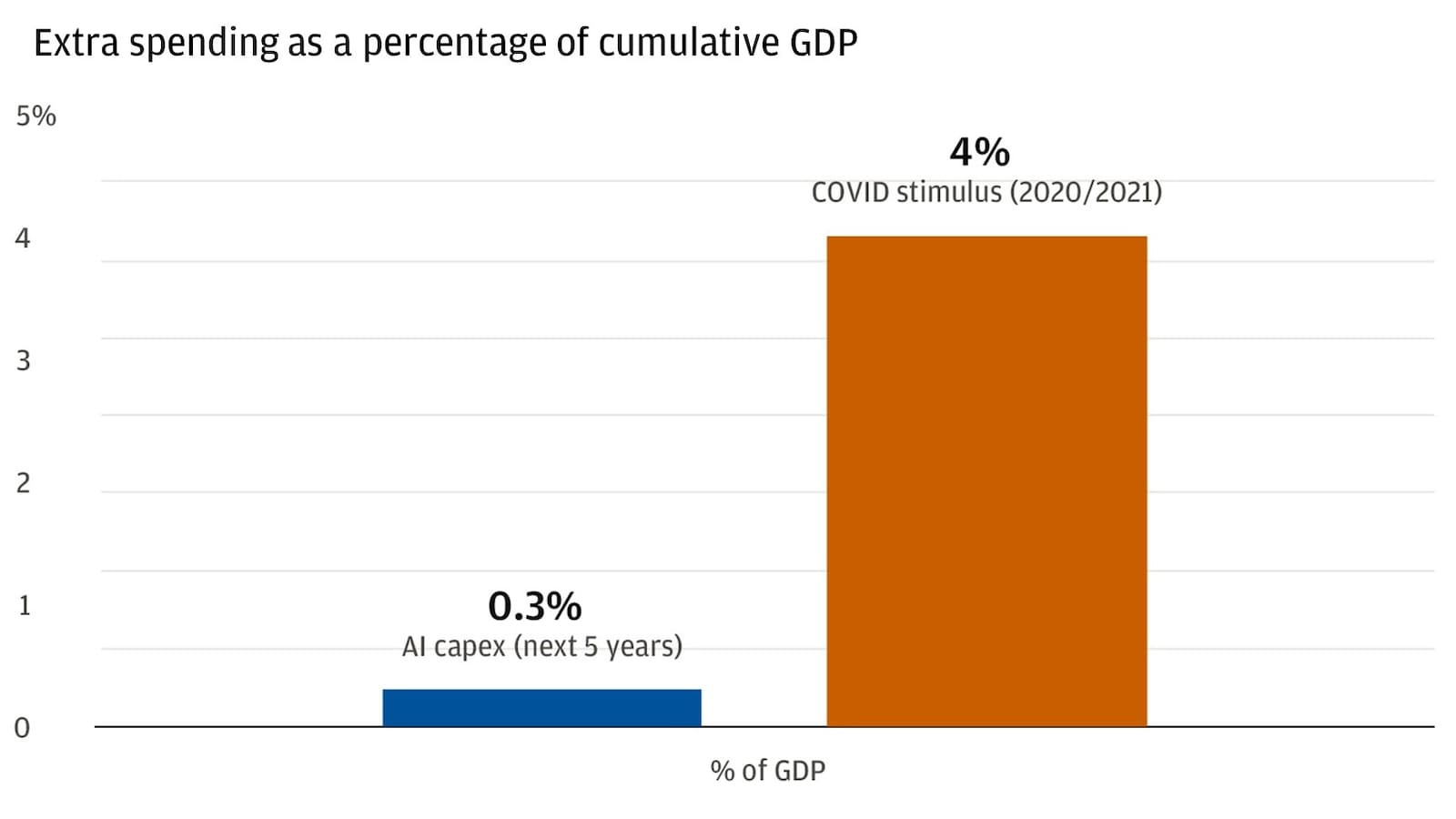

In the short run, AI adoption will likely pressure inflation rates higher. But we think the inflationary effects across the entire economy will be modest. That’s mainly because the AI infrastructure buildout doesn’t look to be that large compared to the broader economy.

By our estimates, the cumulative rise in AI capex spend over the next five years will total about $400 billion, which is just 0.3% of expected cumulative GDP over the same time span. That’s a far cry from a recent spending surge that did prove inflationary. Cumulative excess government spending on fiscal transfers to households during the COVID-19 years of 2020 and 2021 totaled over $2 trillion, or more than 4% of GDP.

In the long run, we believe, AI’s impact should be more disinflationary than inflationary, but that benefit isn’t likely to be realized until later in the decade.

It's early days for capex spending on AI infrastructure

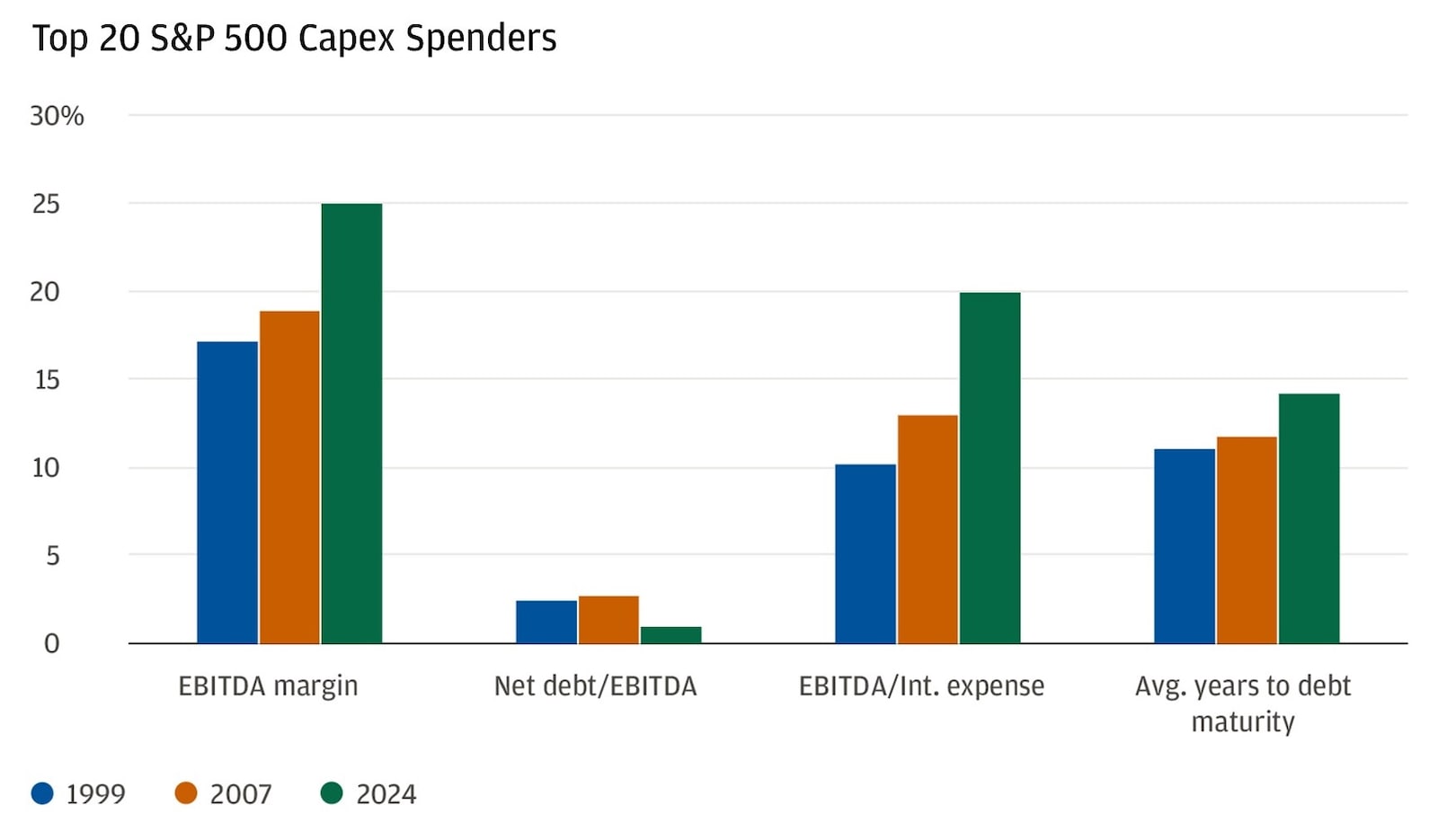

Currently, AI-related capital investment (capex) is being funded by highly profitable companies with low levels of debt. This was not the case in past periods of technology-driven capex, such as the internet buildout of the 1990s.

The 20 largest capex spenders in the S&P 500 today report EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) margins of 26% and net debt to EBITDA (one way of measuring debt leverage) of below 1x. Compare this to the top 20 capex spenders in 1999: They reported 16% EBITDA margins and a net debt to EBITDA ratio of 2.45x.

Today's capex spenders boast strong cash flows and manageable debt

What’s more, the hyperscalers (large cloud service providers) that are investing 50% or more of the overall AI capex are sitting on huge piles of cash, and their businesses generate high levels of free cash flow. These companies are not issuing excessive amounts of debt to fund their capex. They don’t need to. Given hyperscalers’ ability to self-fund their AI initiatives, it is less likely that today’s high interest rates will curtail their investments.

The absence of excess leverage is important because it means that AI-related capex is not, in our view, creating a worrisome debt imbalance in the economy. This makes for a notable contrast with the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. That bubble expanded in part through excess leverage – and ended in a bust.

A discussion of leverage circles back to inflation. While today’s AI capex spend may result in pockets of sector-specific inflation (e.g., in the power sector, where we are already seeing a fierce bidding competition by hyperscalers for long-term contracts), we don’t anticipate that AI will produce meaningful inflationary pressures at the macro level.

What this means for your portfolio

How might you think about AI investments in your own portfolio? AI has already catalyzed a wave of excitement, investment and earnings growth. We want to invest for the long term across the value chain.

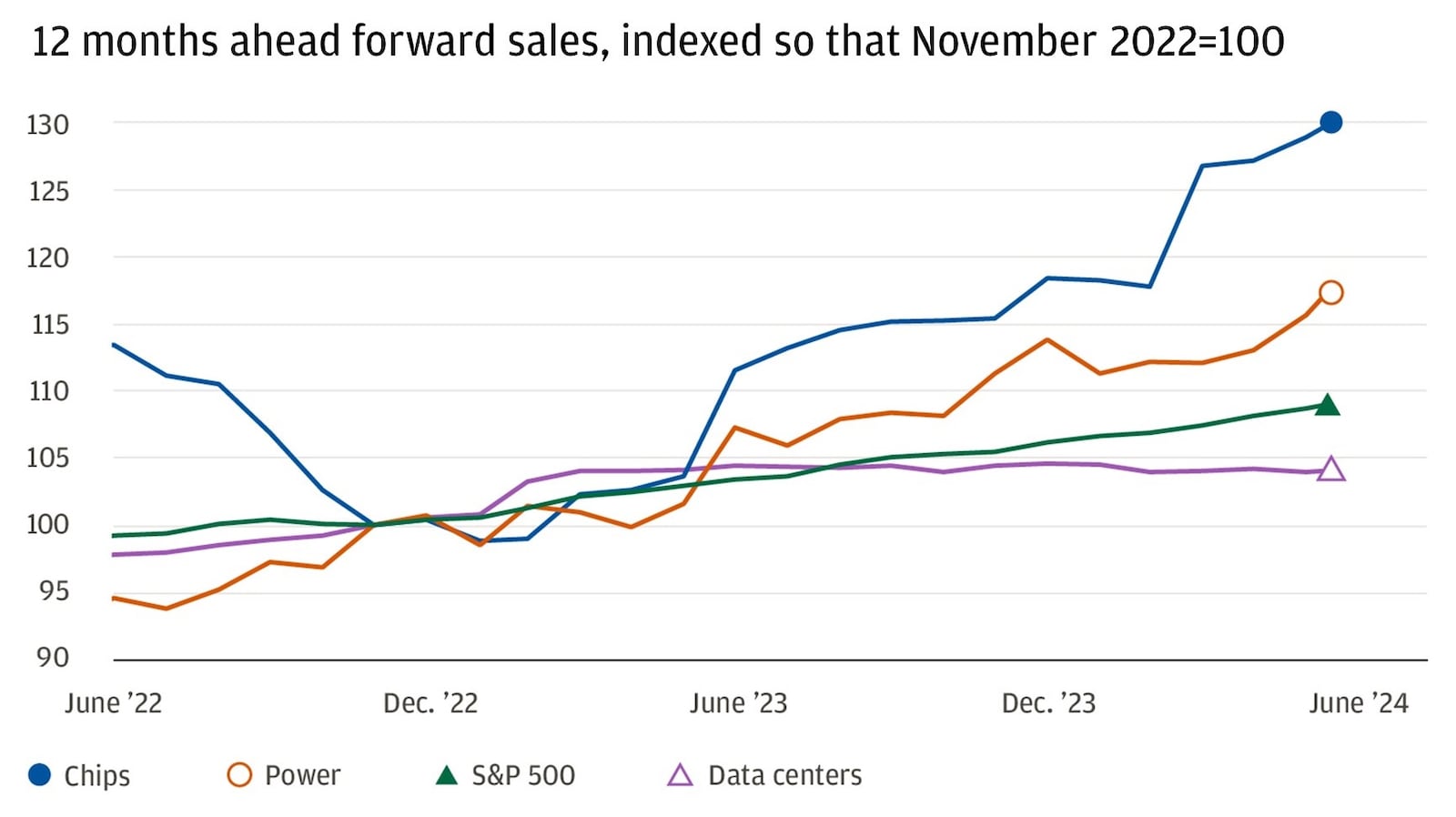

For now, we suggest clients focus on the AI infrastructure buildout: semiconductors, data centers and new power generation – including the many smaller and less well-known companies. Facing increased demand for their products and services, companies in these sectors have been already meaningfully boosting their sales projections.

The below chart shows 12 months forward sales expectations for companies in the three infrastructure categories, indexed to when ChatGPT was released in November 2022. Only one category, data center sales, lags the overall market, while the other two have seen substantial upward revisions.

Revenues are on the rise for AI infrastructure-related companies

Fair enough, the skeptics say. But isn’t all that promise already priced in? Some of our clients worry that AI stocks are too expensive, and the market too concentrated, to justify investing new money in the trend. AI, they worry, is currently in a bubble.

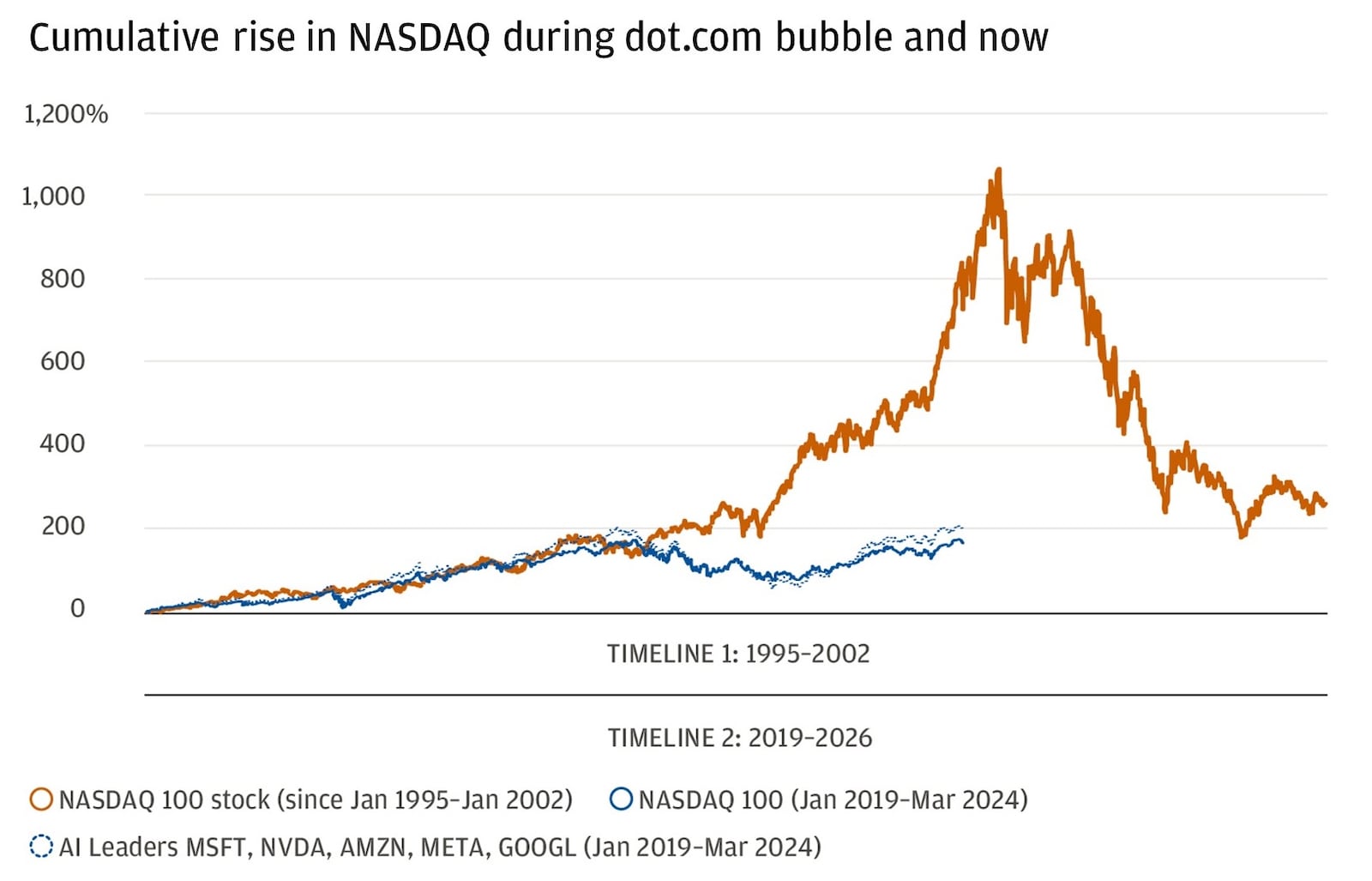

Certainly, the biggest mega-cap stocks, many AI-related, have surged since the S&P 500 hit its cycle low in October 2022. Yet, when comparing the market of today to the 1990s bubble, we see significant differences. During the last five years, the Nasdaq 100 rose just over 200%. That is nowhere near the greater than 1,000% appreciation that preceded the 2000 market peak. Further, while valuations of the AI leaders today are not cheap, they trade at nearly half the P/E multiple of the leaders in 2000.

Today’s market is a far cry from the dot-com bubble

AI skeptics often point out that the market is considerably more concentrated than the historical norm. The top 10 stocks currently make up just under 35% of the total market capitalization of the S&P 500 versus an average of about 20% during the 2005-2019 pre-COVID period. Importantly, though, these 10 companies also account for a greater portion of the index’s earnings, now at 26%, than at any time over that period. In 2000, not long before the dot-com bubble burst, the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 made up 27% of the index’s market cap, but only 17% of its earnings.

We think today’s high valuations for AI-related stocks are justified, given the potential productivity benefits – and the resulting corporate earnings growth –that AI could deliver.

In other words, AI is not a speculative bubble, in our view. It is indeed a revolution, and it has only just begun.

We can help

A J.P. Morgan advisor can help you consider what kinds of AI-related investing make the most sense for you and your family.

Invest your way

Not working with us yet? Find a J.P. Morgan Advisor or explore ways to invest online.

Managing Director, Portfolio Manager, J.P. Morgan Global Wealth Management